The RVU solution

The Medical Post has done comparison rankings of provincial relativity before. But those were based only on fee-for-service (FFS) billings. Alternative payment programs (APP) make up almost one third of Canadian doctors’ clinical income today, even though APPs barely existed in the mid-1990s. It was only last year that the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) started releasing data from its new full-time-equivalent metric, which combines both FFS and APP remuneration.

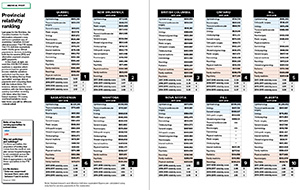

The Medical Post 2019 Relativity Ranking used this new FTE metric to compare the ratio between the average billings of the top three earning specialties and the bottom three in each province. We then ranked the provinces.

Our 2019 Relativity Ranking shows that Quebec doctors have the least variation between top billers and bottom, and Alberta doctors have the greatest. In fact, in Alberta, the top three specialties’ average billings are almost three times those of the bottom three.

Billings don’t equal income, of course. Overhead is not included here. But outside of getting access to doctors’ tax returns, calculating accurate overhead costs for different specialties and different practice situations is difficult. In Canada, overhead estimates by specialty mostly come from surveying doctors. However, some provinces are working on more robust measurement, developing metrics for “model offices,” for example. In such cases, all the various practice costs are identified so that data can be fit into the model. The cost per square foot of medical office space in a town, for instance, is plugged into the model, along with the average cost of equipment, clinic supplies, and a range of other expenses. As factors change—or different communities use the model—you simply adjust the relevant metrics, and you’re left with a good sense of what overhead should be for various specialties in various practice situations.

In provinces where the top three specialties are billing, on average, two-and-a-half to three times as much as the bottom three, the demand for these kinds of measures is going to grow. Medical associations are examining relativity in different ways but the Alberta Medical Association (AMA), with its Income Equity Initiative, has taken the lead over the last few years in its efforts to get a clear-eyed look at the problem.

Alberta’s progress

It has not been easy work for the AMA. The association decided last year that an overhead study it had conducted with Alberta Health was not good enough. “We looked at early results of the study,” said AMA president Dr. Christine Molnar, “and we talked with our joint partner, Alberta Health. We decided it was flawed. The data coming out of it was so flawed it was not useful to us.”

Since then a small group at the AMA has been working on how to better determine expenses. It is looking to repurpose some of the data from the old overhead study and thinking broadly about how to fairly represent overhead which is, in some cases, common across certain groups of doctors, and in others completely unique to a particular specialty.

“I think we’re tending towards a more current business cost model that will be more like a model office,” said Dr. Molnar, a diagnostic radiologist and nuclear medicine specialist. One advantage is that it will help physicians understand what an efficient office should look like.

Of course, overhead is just one component of the Income Equity Initiative. To determine if there is income inequity among Alberta physicians, the AMA is also studying hours of work, length of training and competitiveness. These other components can be more complex to evaluate than overhead. But the AMA is expecting the overhead study and the other three studies all to be done by December 2020.

At that point, the Income Equity Initiative should be able to say something about whether there is income inequity—and if there is, the extent of it—between specialties.

The question then becomes what will the association do about it? Dr. Molnar conceded it is always hard for member organizations to say to anyone that they don’t deserve what they are earning and that it should be reduced. “What we have to focus on at this point is fairness and transparency,” she said. “People have to be able to say: ‘I don’t like the outcome. But it would appear that it was a fair and just process and I’m going to go along with it for now.’”

The results of the initiative and what to do about it must be ratified by the AMA general membership, Dr. Molnar said. Currently the AMA does not have the necessary approval from Alberta Health to reallocate money from one specialty to another, even if the membership approved such a change.

Other provinces

The challenges the AMA faces mirror those in other provinces. Looking at relativity is tough but important work. Ontario has used a number of models—OMA RVS, RBRVS, RVIC and CANDI—to try and deal with relativity. British Columbia had the Relative Value Guide effort in the mid-1990s. Other associations have proposed their own methods for examining and ultimately addressing the issues.

But even when these models are developed, they either aren’t applied or are applied only minimally. High-billing specialties often take legal action against the measures, or threaten to split off from the medical associations. Some specialty sections question the data. All these pressures have made fixing relativity the third rail for medical leaders: It won’t go well for you if you touch it.

Still, the perception of income inequality grates many members of specialties at the lower end of the billing spectrum. Some even argue continued income inequity undermines professional collegiality.

One has to wonder: Is there a better way?

There is—kind of. Relative value units (RVUs) are the backbone of how the U.S. Medicare/Medicaid and most American private insurers determine physician productivity and compensation. Doctors Nova Scotia is aiming to use RVUs as part of the massive effort to update its fee schedule.

One can see the advantages. The RVU system evaluates relativity on a more granular level. Let’s walk through how it does that.

[EMBED]

The case for RVUs

First, all American doctors use the same language to describe their clinical work: the current procedural terminology or CPT. “The CPT system is a nomenclature system so you can describe the services, and it’s a system that is clinically relevant. There’re lots of instructions built in so people know how to pick the right procedure code.”

That’s Dr. Peter Hollmann, a Rhode Island physician who I was connected with when I asked the American Medical Association for an expert on RVUs. He’s a past chair of the CPT Editorial Panel and is currently on the American Medical Association’s specialty society resource-based relative value scale update committee, known as the RUC.

Someone had to take each CPT code and assign it a relative value unit when the system was set up in the early 1990s but even if those initial decisions were off, RVUs are periodically adjusted based on regular comparisons of similar procedures. “You might say this procedure takes me a half an hour and it’s pretty easy, and this procedure takes me half an hour but, my goodness, it’s very difficult, so I think the latter ought to be 30% higher in value. Or this procedure is 20 minutes and this other procedure is 50 minutes and it’s pretty much the same intensity, so I think the latter ought to be two-and-a-half times its value because it takes me two-and-a-half times as long,” Dr. Hollmann explained.

There’s a myth that the RUC actually uses stopwatches to time doctors as they complete tasks. It doesn’t. The valuations are mostly done from surveys of doctors who are familiar with the procedure, though sometimes databases and operating room logs are used supplementally.

But if survey results are relied on to determine RVUs and these are used to determine fees, is there not a risk some would want to skew the results?

“Let’s go over this attempt to game the system, even if it’s unconscious,” Dr. Hollmann said. “If I’m comparing something I do to another thing that I do commonly, I think you’re going to get pretty accurate (results),” he said. In other words, it is likely comparisons of procedures within a specialty are accurate. But what about when you compare, say, ophthalmology and urology?

“Your society presents this to (the multispecialty RUC). These are people who have been listening to these explanations and surveys before,” said Dr. Hollmann. It’s a technical expert panel, he noted, that can spot flaws in the information. Ultimately, it requires a two-thirds majority vote to approve a value. “If somebody takes the information and sort of spins it, you’re not going to have a very easy time getting away with that.”

All of these factors—from the time required, to the intensity to the requisite expertise—comprise the “work” component of a RVU. The panel also evaluates a “practice expense” component, which varies depending on the cost of equipment, supplies and support staff, as well as a small “malpractice” component, which accounts for the risk associated with a procedure. Those three elements determine the final RVU.

Then you just multiply the RVU by the “conversion factor” (currently 36.0391) to produce the dollar value. This measure allows U.S. Congress (which determines the conversion factor) to control the annual expenditure on Medicare. For example, the CPT code 99213 is used all the time by American doctors. It’s for a followup office visit for an established patient. The current RVU for 99213 is 2.09. (So 2.09 X 36.0391 = $75.32 USD). RVUs also go through a geographic price cost modifier to adjust for regional cost variations.

RVUs are primarily tools for allocating expenses and cost benchmarking for Medicare. The fact that they work to measure productivity and to calculate physician compensation is actually secondary. But this method is so effective that nearly every healthcare system in the U.S. uses it. “I have always been in practice but I also worked part-time at Blue Cross Blue Shield in Rhode Island, an insurance company,” noted Dr. Hollmann. “Once this system came along, I said, ‘We’re crazy not to use it the way Medicare does, because you’ve got people investing millions of dollars of volunteer time and work … and it’s about as accurate as you’re going to get.”

Doctors Nova Scotia

The only province that has looked seriously at using RVUs is Nova Scotia and it is currently on hold in that province for a couple of reasons, according to Kevin Chapman, director of partnerships and finance for Doctors Nova Scotia.

One, the EMR landscape in the province is in transition. In 2016 Nightingale, formerly one of the leading EMRs in the province, sold its Canadian assets to Telus Health. So all Nightingale users have to migrate to either Telus’ Med Access EMR or the QHR Accuro EMR. “Essentially every doctor has to migrate and that’s supposed to be done by the end of December,” said Chapman.

Two, Nova Scotia doctors recently completed their fee deal negotiations and while the provincial government had originally been keen on developing a new fee schedule, in Chapman’s view, it seems not to be so keen anymore. Changes in government administration and contract negotiations has resulted in inertia. (He noted that setting up a new schedule via RVUs involves a lot of “nitty gritty” discussion, and that both sides should be in agreement that doing so be treated as an information management project rather than a cost-savings project. Currently, Chapman argued that the old manual is out of date, and doctors are having to use lookalike codes that don’t match the operative record and thus can become a problem during audits.)

That said, Doctors Nova Scotia plans to start pressing the government to move on this again in the new year.

Doing something like this for a larger province such as Ontario would be a massive enterprise.

Tweaks and criticisms

Even though the RVU system can be used as a clinical productivity-based compensation system, Americans often tweak it to adjust for other important parts of physician work besides CPT coded services. “At some practices, we would say, ‘We’re going to say Dr. Peter Hollmann’s teaching is worth X number of RVUs or his consulting with the hospital is worth X number of RVUs,’” said Dr. Hollmann.

He also said the system has gotten more nuanced in recent years. “For a long time the Medicare payment rules didn’t recognize a lot of the extra work that went into things that occurred between office visits, such as coordinating care and phone calls and stuff like that. Obviously, some specialties have more of it than others,” he said. “Finally, in the last several years, there’s been more of a recognition of that and that’s improving the payment for specialties that did a lot of this work.”

As well, while private insurers and hospitals that are competing with one another may pay doctors more than 100% of the RVU that Medicare pays, they generally still use the RVUs as their marker for relativity between services. (Medicaid rates can be as low as 50% of what Medicare pays, for example, and private insurance companies often pay more than Medicare.)

The RVU system is fairly new. It was developed by William Hsiao, an economist at Harvard School of Public Health, and his colleagues in the 1980s. There are, of course, American doctors who complain about it but Dr. Hollmann’s retort is twofold: What system would you use instead, and do you remember what Medicare was like before it began to rely on RVUs?

Canadianization

The basic units of work for Canadian doctors are much the same as for American doctors. So if there’s concern that somehow using an American RVU system doesn’t match with Canadian values about healthcare and equity, it is easy enough to use modifiers while maintaining RVUs as core markers for clinical productivity.

Another concern for Canadian doctors is that because the RVUs are not directly linked to pay, the power of the U.S. Congress to adjust the conversion factor gives government absolute control over the size of the Medicare budget. Congress adjusted the conversion factor up last year but when they adjust it down that forces American doctors who bill Medicare to eat the cost. This is a concern of American doctors, but most have the option to avoid doing Medicare work and instead provide care for patients with health insurance.

Such is not true for Canadian doctors. Giving a Canadian province complete control to set a provincial conversion factor is plainly unworkable. There would have to be arbitrators or tribunals involved or some acknowledgement that provinces can’t reduce conversion factors when health system utilization is rising.

There are some elements of the RVU system, such as practice expense tracking, that are evident in the “model office” work being done by some medical associations. There are definitely challenges with using RVUs in Canada, but as medical associations struggle with ways to address relativity, they should not be afraid to piggy-back off this clinical relative value work already being done.