Gender pay gap in Canadian medicine—yes, it’s real!

Despite the gender gap in physician earnings being of concern to many in Canada, its existence is far from universally accepted and until recently there were no studies published covering all physicians/regions or that addressing earnings rather than billings. This may explain the lack of serious consideration or remedial action by medical associations and governments in negotiations, or tariff and compensation processes.

I discussed this issue, in a limited way, in a previous article. However, recently with my colleagues from McMaster University (Danielle O’Toole, Meredith Vanstone and Arthur Sweetman) we were able to conduct a broad national study and covers all physicians1.

Read: Boris Kralj: Defund relativity

This study is unique not only in its broad coverage, but also as we are able to measure earnings net of overhead costs, rather than gross billings that have been used in all previous Canadian literature on the topic. Additionally, we were able to control or adjust for work effort (hours and weeks of work) and physician characteristics such as age, marital status, children, geography, incorporation, etc.

We utilized 2016 Census of Canada data linked to CRA taxation files to estimate the gap in earnings, net of practice overhead expenses, between female and male physicians.

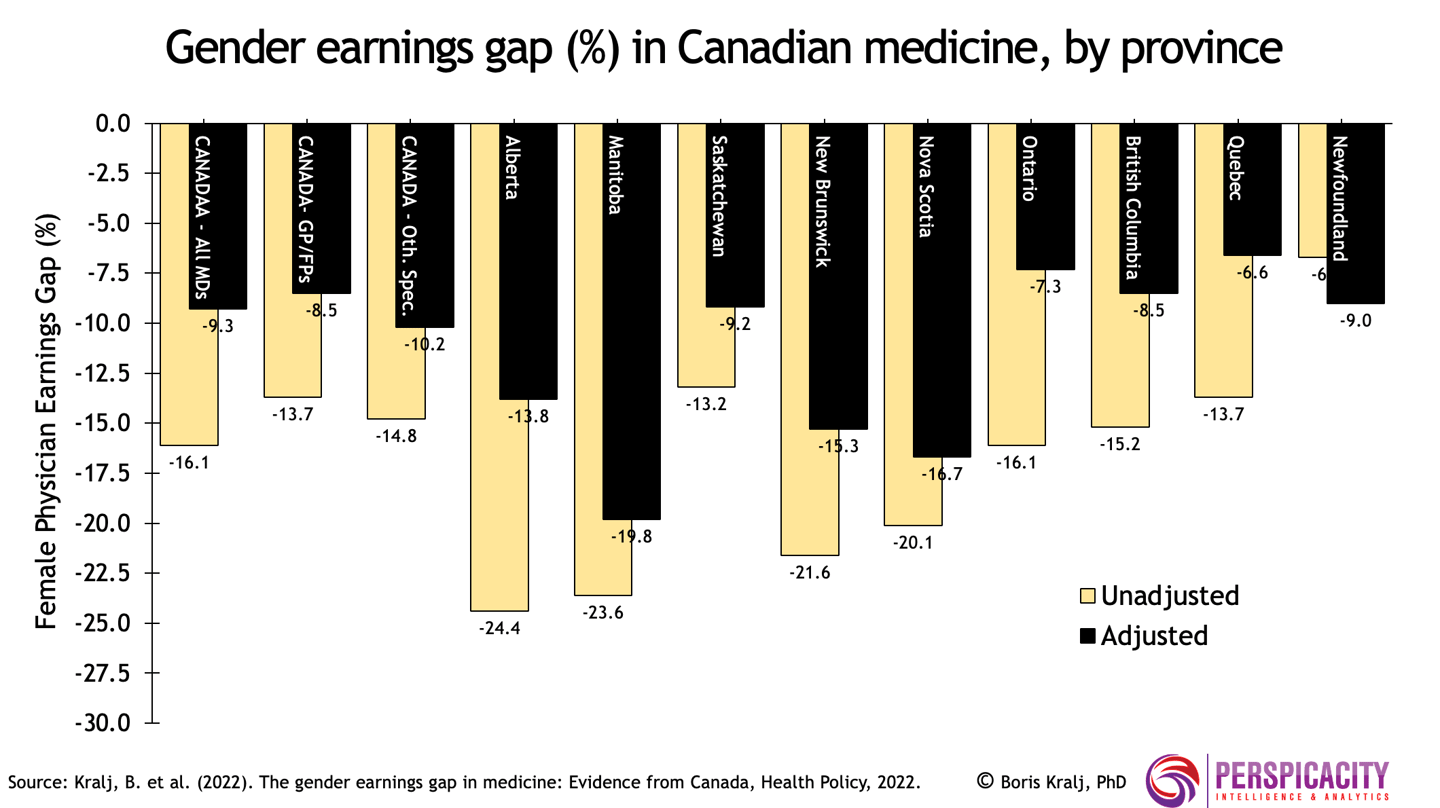

Adjusting for demographics and hours/weeks of work, we found that on average female physicians earn about 9% less than their male counterparts

Nationally, the adjusted gap is slightly larger for specialists at 10.2% than for family physicians at 8.5%. These estimates of the earnings gap at the mean of the income distribution mask important differences across the earnings distribution. Females in Canadian medicine earn less than comparable males at all points of the earnings distribution, but the gap widens notably at the higher end. This may be indicative of under-representation of female physicians in senior roles.

Variation in the gender earnings gap, unadjusted and adjusted, across provinces is shown in the figure below. Manitoba has the largest adjusted average gender net earnings gap at 19.8%. Quebec has the smallest at 6.6%. For Ontario, unlike nationally, the earnings gap for family physicians is larger than for specialists. This finding is consistent with a recent study from Ontario that was based on gross billings2.

We speculate that the variation across provinces in the adjusted gender pay gap may be due to differences in the amount and type of non-FFS payment (i.e., capitation, salary, etc.) and in internal fee setting structures.

Also, provinces with enhanced efforts to address relativity may indirectly reduce gender earnings gaps. Based on our research and that of others, we are of the view that improved tariff/fee-setting processes are the key to closing the gender pay gap and addressing pay equity.

Some jurisdictions, such as British Columbia and Ontario, have carved out specific amounts to address “relativity”—pay inequities between specialties. These should be expanded to also include funding dedicated to closing gender inequities. Beyond the macro-level carve out for addressing the gender pay gap, there needs to be a fulsome micro-level, evidence-based data-driven analysis of tariff/fees allocation structures to identify, quantify and close gender pay inequities at the individual service level. Currently, these structures tend to be based on anecdotal and less than rigorous data analysis.

At the same time, a move away from FFS payment to non-FFS payment, such as capitation for family physicians, would likely be constructive in reducing the gender pay gap

In conclusion, the gender pay gap in Canada’s publicly funded and privately delivered medical system is real and pervasive, it is significant from both a statistical and policy perspective nationally and across provinces.

Boris Kralj (PhD) is an adjunct assistant professor, McMaster University, department of economics and founder & principal consultant, Perspicacity Intelligence & Analytics.

References:

-

See Kralj, B., O’Toole, D., Vanstone, M. and A. Sweetman (2022). “The Gender Earnings Gap in Medicine: Evidence from Canada”, Health Policy, Volume 126, Issue 10, pp. 1002-1009.

-

See Steffler, M., Chami, N., Hill, S. et al. (2021). Disparities in Physician Compensation by Gender in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Network Open, 4(9) 1-10.