5 steps to help pharmacists validate negative thoughts and turn them around

What if I could control the way I felt by controlling the way I thought?

Like a remote control for television, our negative thoughts take us to the shows playing in our heads.

The good news: we can train our brains to better handle negative thoughts, so we end up watching the shows we want instead of being stuck in a bad movie, too deeply committed to walk away.

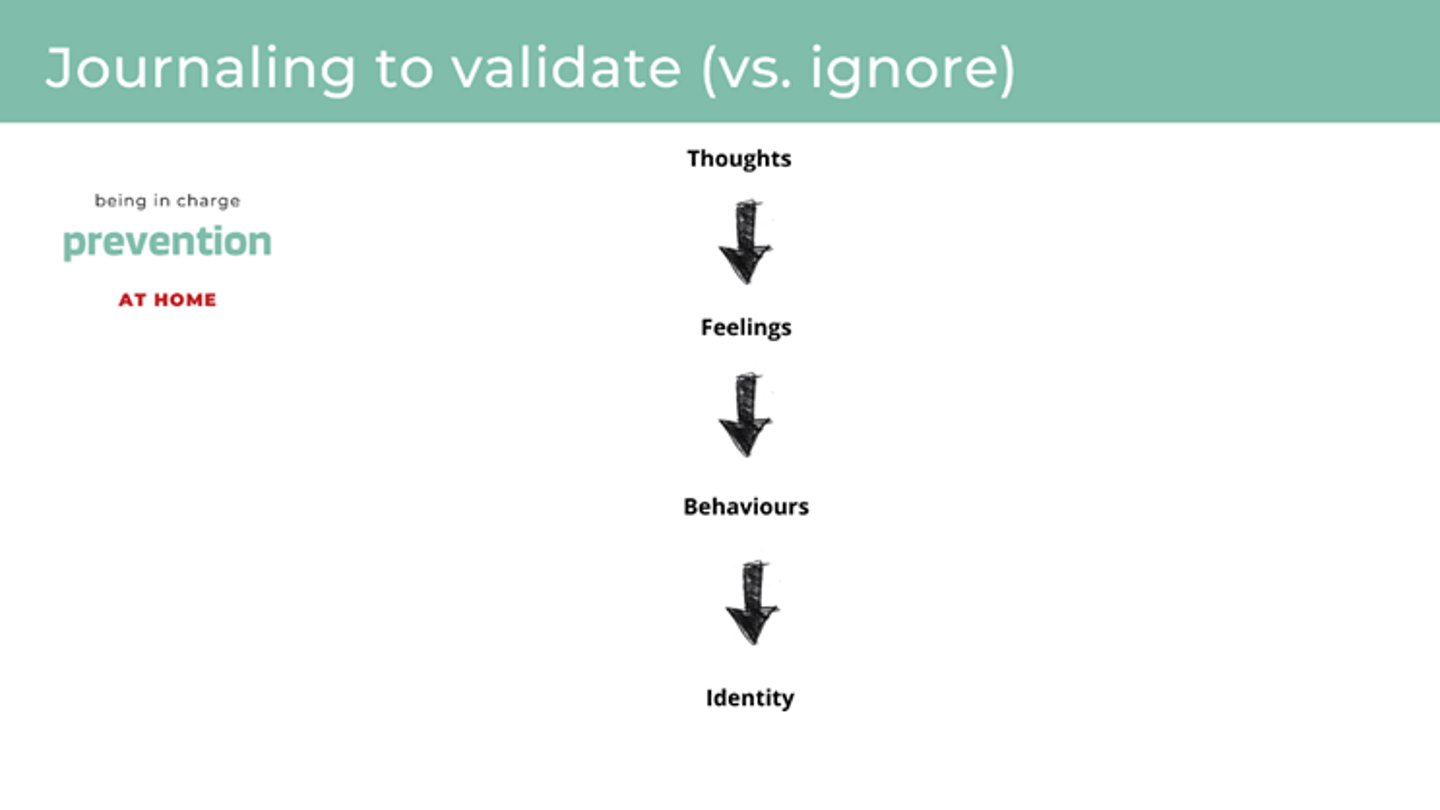

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is something pharmacists recommend. Scientific literature proves its place as a first-line therapy in mental health. The principle is that our thoughts influence our feelings, and our feelings influence our behaviours. Since, over time, those behaviours carve our identity, it is important to deal with the first step in the cascade properly: the thoughts. This means much more than “think happy thoughts.” It means validating negative thoughts, instead of trying to ignore them.

Over time, I have practised journaling through the problems of the day and tried to remember this principle: validate versus ignore. Here are five key journalling questions in that process:

- What can I control?

If I cannot control it, then I will choose not to worry about it. I will focus on what I can control instead and have confidence that I will deal with the rest when it is time to make a decision.

- What does this look like with emotion removed?

When we mix emotion with a problem, it transforms into conflict. But leaving the emotion out removes the catalyst for conflict to be created and it simply stays as a problem to solve.

- What would a trusted colleague tell me?

This allows us to think through Question 2 by clearly removing ourselves from the scenario.

- What is the worst that can happen?

By setting the hazard bar as high as possible and then searching for examples from our past as data to disprove this high bar, we rationally see that we have exaggerated.

Example:

“This pharmacy is so busy I’m going to make a mistake that will hurt someone.”

Through rational CBT journalling exercise:

“Well, we do 200 prescriptions per day and none of those days are exactly easy. That’s 1,400 prescriptions per week and A LOT per year. Less than 1% (i.e., 0.5 out of 200) of those prescriptions come back with complaints, let alone serious enough complaints to cause harm. So maybe I’m exaggerating.”

- What are the actual chances of that happening?

Sketching life as data proves life’s intangibles tangibly.

-What are the chances of (insert negative thought) happening?

-Ok, and for that to happen, what are the steps that need to happen that lead up to it?

-And what are the chances of those steps happening?*

-Now what are the chances of each of those steps all happening, one after another in the right order?

*As a note, sometimes asking ourselves the fifth question two or three times helps us to narrow down the true percentage risk of the catastrophic mental exaggeration.

Journalling with these types of questions invites rational thought. With time, we train the brain to use these questions automatically, without the use of paper and pencil (or electronic versions of p&p).

These key questions serve as parents, monitoring the party so the music doesn’t get too loud, people don’t drink too much, and jump into the pool from the roof in their underwear.