Clinic room designs must fit care models

Dr. Diana Anderson

Dr. Diana Anderson“Where should I sit?” my geriatric patient asks as he enters the clinic room, his walker just barely clearing the doorway.

I glance around at our choices—there’s the clinician’s chair-on-wheels positioned towards the desk with the computer monitor, the examination table itself, or the designated patient chair. I know that today my priority is to discuss advance care planning and goals of care—a discussion that warrants equal footing and a potential surface for reviewing paperwork. Sitting on the exam table for these discussions can be physically challenging for frail patients and is not conducive to discussion equity. The patient chair is an option, only its position next to the desk or across from it implies a hierarchy and awkwardness in formulating conversation.

And wait—my patient has brought a family member, where will they sit?

As medicine increasingly becomes a family affair, especially in the realm of pediatrics and geriatrics, how can clinic room design foster these new models of care? As the emphasis on advance care planning grows with communication of difficult topics now being taught as a clinical skill, there is immense value to re-envisioning the primary care clinic room to support these changes. As a health system we have mainly concentrated on throughput and outcomes required by clinic encounters and not necessarily the experiences of the various user groups—space design and care appear to be more divergent than ever. Now I believe it is the time to focus on the clinic environment to better support all-inclusive care.

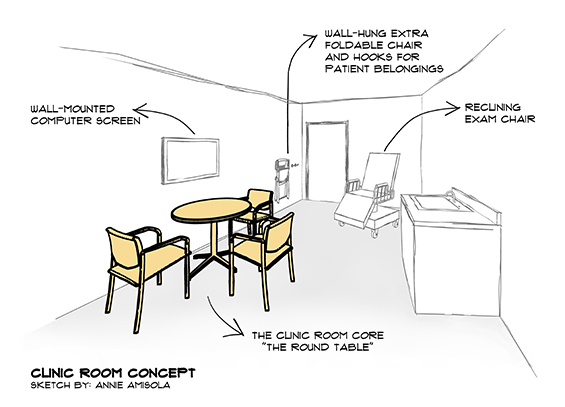

Innovative clinic room design can (and should) advance the practice of collaborative thinking and decision-making in medicine by abolishing the “doctor behind the desk” phenomenon. The round table makes an appearance in rare instances of new clinic design, but could become a standard with some clinician advocacy—at least three chairs around it, all of equal design (sturdy, with arm rests). Reminiscent of the Arthurian legend around which knights congregated, the implication was that everyone who sits there has equal status. A computer screen can be used to support the discussions, preferably mounted in a way to be referred to if needed or even retracted—but should not dominate or obstruct the physician-patient interaction.

Clinic rooms should expect family members and be prepared—foldable chairs can be hung on the wall or stored in custom-designed millwork, for quick and easy access. And the examination table often feels like the awkward elephant in the room in its size and placement. In busy clinics where patients rarely undress and gown for a full physical exam, this design element could transition to a specialized reclining chair model. A single procedure room elsewhere in the clinic can be maintained when specific examinations are required.

And while I am reflecting on my “clinic design wish list”, a few wall hooks for patient canes, outerwear and bags, are simple enough and would enhance the encounter. Effective patient encounters do not happen by chance—the impact of design should be realized.

We cannot expect a generic room design to adapt to the changes in medical practice. Can health architects design the clinic room for equitable patient interaction and incorporation of family? Yes, we most definitely can. But a paradigm shift in thoughtful healthcare design is needed with the incorporation of clinicians at the drawing board. This will ensure patients and their families enter clinic rooms which intuitively invite a seat at the table—supporting, not hindering, patient-centered and team-based care.

Dr. Diana Anderson is a Canadian currently doing her geriatric medicine fellowship in the U.S. She thinks of herself as a “dochitect” as she is a board-certified internist, a licensed architect and also a board-certified healthcare architect. Find out more at www.dochitect.com.